With Kind Regards

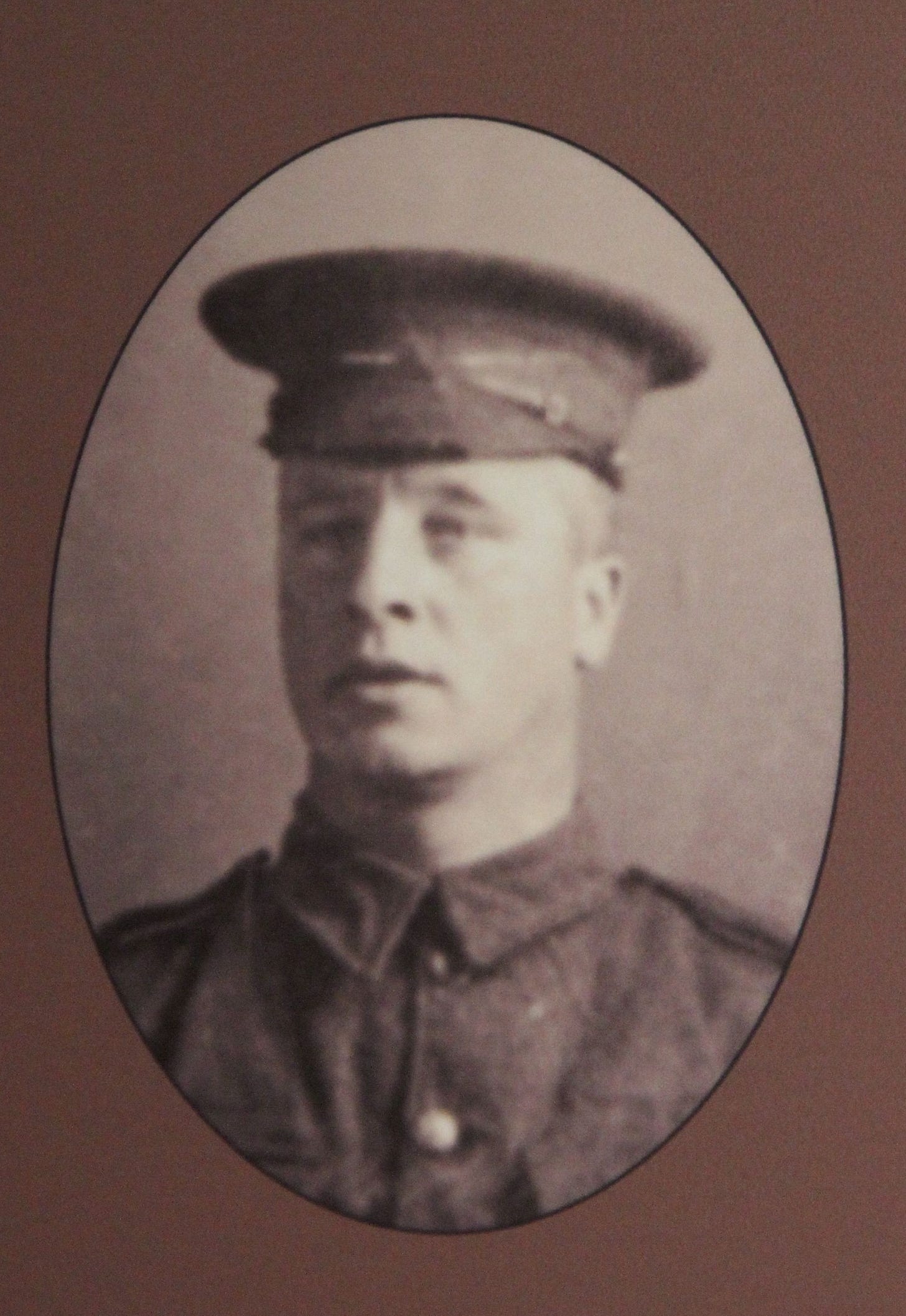

Private Francis Thomas 'Mayo' Lind

Private Francis Thomas ‘Mayo’ Lind

Royal Newfoundland Regiment

Born Betts Cove, Little Bay Newfoundland; Mar 9, 1879

Killed in action – July 1, 1916

Buried at Y Ravine Cemetery

Louvencourt, France – 29th Division Headquarters - June 29, 1916

By day, by night the ceaseless rumble of the guns thundered across the fields of the Somme before reverberating back through the bustling French village. At the canvas hut, gusts of wind caused its’ entranceway to flap back and forth and back and forth again. With the wind came the rain, and successive bands rushed through, drenching the men as they scurried about in the final hours of their rest. All the while the business of an army at war preparing for a colossal battle continued unabated. Trucks loaded down with war materials grumbled through town, heading for supply dumps situated closer to the front lines. The streets were alive with a parade of men, voices and accents from across the isles all gathering to compete in the big show. Staff officers smartly moved about, each followed closely by their aides-de-camps. And yet back at the YMCA hut, the one with the flapping flaps, a long line of men snaked its’ way from the entrance, each soldier safeguarding letters destined for loved ones back home. For many, these would come to be their last words…final thoughts of love and care meant to ease the burden of what may or may not come to be. Standing amongst the procession was a sturdy, middle-aged Newfoundlander, a celebrity of sorts, holding in his hand the newest installment of his ‘Newfoundlander in the Trenches’ sort of...dare I say…blog. The man was proud islander, accountant, soldier and writer Private Francis Thomas ‘Mayo’ Lind.

Private Francis ‘Mayo’ Lind was not just a soldier serving in the Newfoundland Regiment. He was his nation’s first independent citizen journalist…or what we would today call, a blogger. Between quiet breaks in his training in Scotland to the time spent travelling on troop ships travelling east the Dardanelles to wedging himself into dugouts carved into the side of a trench on the Gallipoli peninsula, Mayo would write letters destined for friends, family and his fellow countrymen back home. He would write thirty-two of these letters, each providing a unique and compelling account of his experiences and perspectives of his service in the war. They would eventually become published in the island’s most read newspaper, the St. John’s Daily News and with each new letter placed into print, the popularity of his writing would rise. In almost no time an entire nation came to eagerly await the next installment of Mayo Lind’s insights on the war.

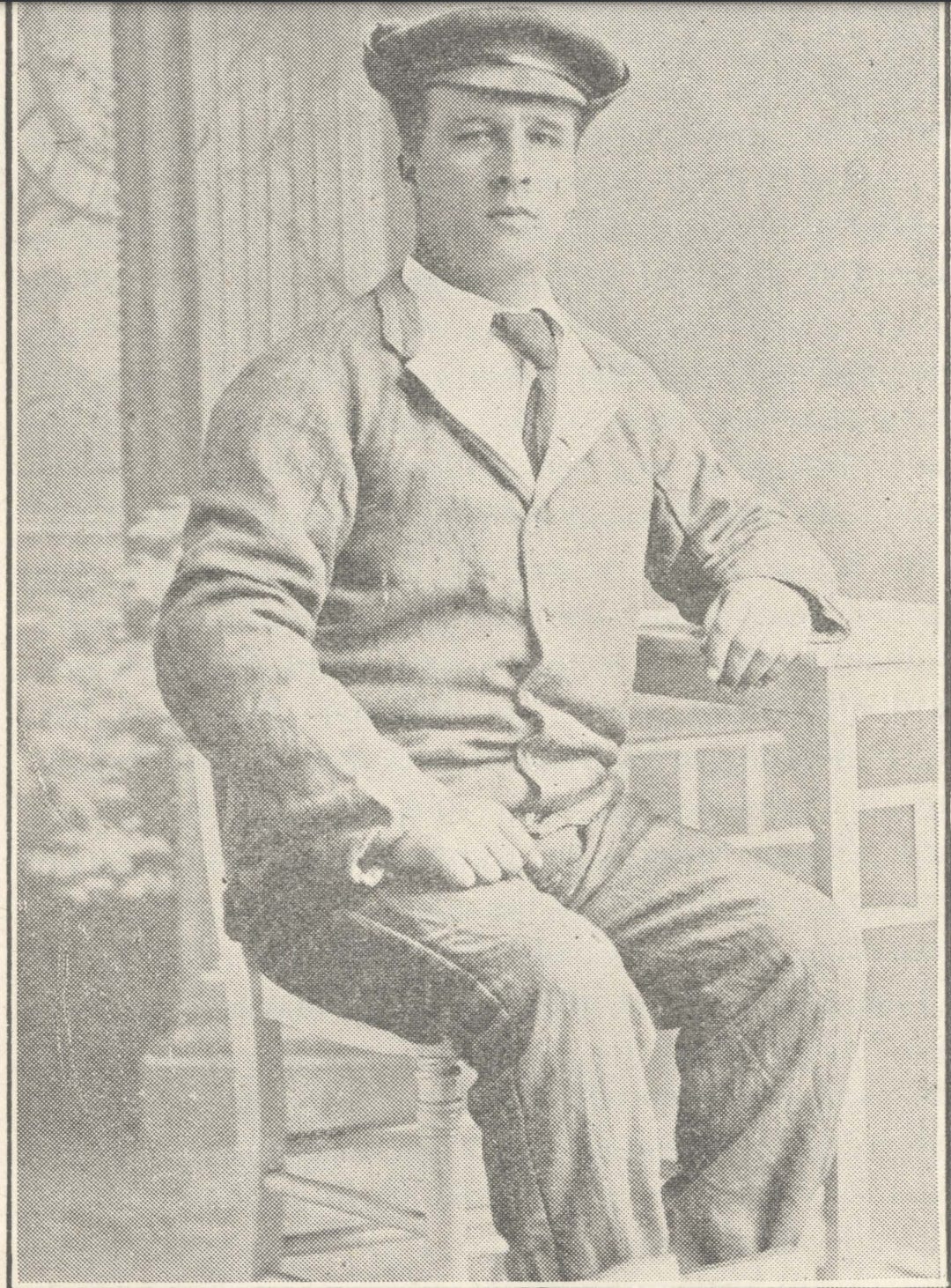

A little about Mayo…a man with an interesting but wholly deserving nickname. Francis Lind was born and educated in a tiny fishing village clinging to the edge of a rugged inlet called Betts Cove. Like many of his contemporaries, when he reached adulthood, he moved to the city to seek employment. He found work at the Ayre and Sons in St. John’s, a grocery chain operating across the dominion. As we are aware, war broke out on the continent in 1914. Lind was 34 years of age at the time, not yet married, however there is evidence he had a lady-friend named Maude. She was 12 years his junior and while there are accounts that they were engaged, no direct evidence of this exists. Thus, with no children nor familiar obligations, when the call was made for volunteers to join the newly formed Newfoundland Regiment, Francis wasted no time in signing up.

He was an interesting chap and his unique personality is evident in his early letters. While he was not a professional journalist, he demonstrated that he was well-read, interested in history, culture and religion and took every opportunity to relate his observances and opinions. He began to write as soon as he arrived in Scotland and continued to pen posts on a regular basis as the regiment proceeded from camp to campaign, transporting to Egypt and then Gallipoli. His notoriety took off when in his fifth letter, he griped about the poor quality of the tobacco in Scotland. He commented how he wished they sold Newfoundland’s own Mayo’s Tobacco instead of the ‘horrible weed’ they were ‘tortured’ with. This letter, once published in the Daily News, went ‘viral’ causing the readers to rally to his cause, collect funds and then send a supply of Mayo Tobacco to Mayo and his mates overseas. When the package arrived, Lind passed out the chewing tobacco (with no unpleasant after-taste!) to the men in the regiment and from that day forth, he earned the new moniker ‘Mayo’ Lind.’

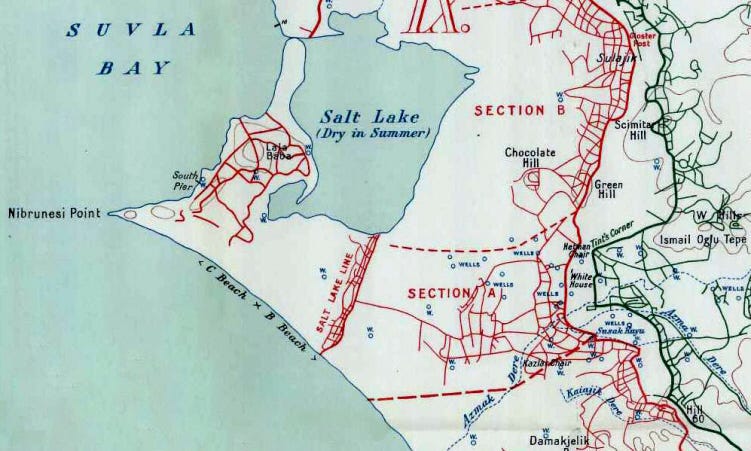

Lind honed his informative and observant style of writing while encamped in Egypt. He intertwined his stories with accounts of the ancient history of the country, the people, the camels, the pyramids and how he was able to visit places mentioned in the bible with the day-to-day happenings of the regiment. He also knew that people back home love to scan his articles in the hope that their boy was mentioned and thus added regular mentions of fellow soldiers within his pieces. The popularity of his articles grew most when the regiment joined the battle against the Turks in the autumn of 1915. In the spring of 1915, under the direction of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir Winston Churchill, the Allies opened a second front against the Axis powers by attacking the Ottomans on their home turf. To be a bit more accurate, they unsuccessfully tried to force the straits that led to the critical capital city of Constantinople, unfortunately lost a few destroyers in their attempt, spent the next two months scratching their heads trying to determine what to do next, thereby giving the Turks sufficient time to reinforce the previously undefended peninsula...(breathe!) and then had the brilliant idea to invade on the 25th of April. Led by a contingent of primarily Australian and New Zealand troops, they landed at a place later to be named ANZAC Cove. Quickly jumping to the result, it was a colossal failure. Yet, not suffice with achieving only ‘colossal’ failure, on August 6th they decided to open a second front in a place called Sulva Bay located 8 kms to the west to better support their feeble first foothold. The Newfoundland Regiment joined the fray here on September 20th.

Upon arrival on the flats at Sulva Bay, The Newfoundland Regiment, as part of the 88th Brigade, were ordered to occupy a series of reserve trenches. One week later, Mayo Lind, snuggly wedged into a dugout in one of the trenches, penned his first letter from an active warzone. Like most conversations, as was his style, the topic of weather was discussed. While visitors to the peninsula may perceive that as it the terrain was semi-desert that the temperatures would be rather warm. However, that was only half the story. In the daytime the temperatures would soar to scorching hot levels, baking the men creating perfect conditions for flies to thrive and pester the men. In the evening, the conditions would dramatically change with the temperatures plunging to freezing cold levels. He also made sure to mention by name the first few men killed and or wounded in the fighting. Notable is that the Newfoundlanders did not do a lot of fighting while stationed in Gallipoli. There was not a lot of fighting to be had. It was more like trying to not get hit by Turkish snipers or to try to snipe unsuspecting Turks imbedded in positions higher up the cliffs. Sulva Bay was a wide and shallow bay that slowly and progressively rose to heights that overlooked the bay. Any soldier careless enough to poke his head above the parapet would meet a very unfortunate circumstance. Lind wrote in a matter of fact, folky way that seemed to bring readers along with him in his adventures. Readers of the Daily News back home ate this up and rucked to pick up the next copy of the newspaper when a new letter from Lind was published.

The Gallipoli Campaign is notable in its’ futility. The vaunted British Empire failed to secure the beach-hold on the Peninsula and lost over 60,000 men killed in the attempt. They also suffered a disgusting 54% casualty rate. This bruising failure was also born on the nascent Newfoundlander Regiment who lost 49 men being killed, 93 wounded in the field and another 350 lost to disease and trench foot. We may not think of a desert-like landscape as an area prone to rainfall, however on November 26th a massive and violent storm befell upon the peninsula. Torrents of rain hammered the area, where the Newfoundlanders and fellow Brits, holding the lower ground were saw their trenches and dugouts flooded by the gushing rivers of rainfall. Men and material were swept away from the deluge. Those able to hold their positions had to endure the weather quickly transitioning from rain to a frigid cold front where the rain transitioned to sleet and snow. The waterlogged trenches became a slurry, often frozen mess. The result saw Lind and 150 other men from regiment be put out of action from frostbite and trench foot. Lind was evacuated from the peninsula on Dec 13th, 1915.

One of the notable complaints about reading history, especially the Great War, is that the reader often gets pilloried by an obscene array of morbid statistics. The numbers are so large that it is often a challenge to remember that these numbers actually relate to the wartime experience of individual persons. Mayo addresses this reality by giving us a ‘man on the street’ perspective on the impact that Gallipoli had on the regiment. After watching his feet turn from rosy, pink to black and blue after he survived, day after day in waist-deep freezing cold rainwater Lind, understandably, suffered from a bout of trench foot. This was his burden, however when you consider the travails and trials of the scorching hot days, freezing cold nights, snipers, incessant shell fire, disease brought about by poor sanitation and limited access to potable water…one can only then appreciate what these lads had to suffer through. In his twenty-first letter, written in Malta on Feb 10, 1916, Lind related the circumstances in a simple-to-understand perspective. “When we left Alexandria last September for the Dardanelles, the platoon to which I belonged to contained 68 men, good solid men in perfect health. When I left on December 10th for the hospital, I left ONE man left fit for duty. I was the second to last man knocked out.”

Mayo was sent to the island of Malta to recover before being moved to the Greek port city of Salonika (modern day Thessaloniki). It was within these letters (blogs) where Mayo more resembled the author’s travel blogs than the typical wartime memoirs produced by his contemporary counterparts. Each letter was less a ‘who did what, where and when’ than an opportunity to showcase his interest in local history. Whether it be in his letters written in Scotland, Cairo, Alexandria, Malta or Thessaloniki he made a point to provide with readers with historical context to the locations. At Scotland he recounted a list of historical curiosities contained within Edinburgh Castle, including a crown first wore by the Bruce to Cairo in Egypt where, in utter amazement, Mayo talked about how so many stories in the Good Book happened in the exact same place he was wandering about. Mayo did not only want his fellow Newfoundlanders to learn about what the Regiment was up to; he wanted to invite them to join him on his travels.

The Immortal Thirty Minutes

His income may have been earned counting beans for Ayre and Sons Ltd (a grocery company that would one day become part of Loblaws, the largest grocer in Canada) but Lind had an entirely different passion and purpose, writing. He had the instincts of a professional journalist, drawing his readers in with a sequence of interesting stories, references to local or notable individuals and then hooking them with teasers to ensure long lines would queue up at the local news proprietor to pick up the next copy of the Daily News when word got out that it was publishing another Mayo Lind letter. Mayo wrapped up his final letter with the statement, “I will ring off this time but will write again shortly, when I hope to send you a very interesting letter. Tell everybody that we may feel proud of the Newfoundland Regiment, for we get nothing but praise from the Division General down. With Kind regards.” While we would never get to hear about that ‘very interesting’ story, the memory of the pride Lind spoke about would be coupled with the legacy of one of the most heart-breaking displays of mass senseless killings ever experienced in the history of the Great War.

The Newfoundland Regiment was transported to Camp Mustapha in Alexandria after their evacuation from Gallipoli. It was here where they rested and tried to recover from the costly campaign. With the regiment losing approximately 50% of their manpower to illness, disease, conditions and bullet/shrapnel wound, the affected men, including Lind, were sent to hospitals in Malta and Greece. In little under two months, they would receive their next assignment. They were heading to France. The HMS Alaunia transported the regiment to Marseille, France, arriving on the 22nd of March. They would take almost two weeks to find their way north, ending where we started, the village of Louvencourt. As noted, this village acted as the Divisional Headquarters for the 29th Division. The next three months would be spent training and preparing the men for the operation, forever known to history as the notorious Beaumont Hamel in the Battle of the Somme.

In the historiography of the war, in media and academics, we, as Canadians, tend to primarily focus on two great battles from World War One. One was a historic victory where the Canadians prevailed, winning the ridge after so many others tried and died in vain. This, of course, was the Battle of Vimy Ridge. The second battle that manages to slip itself into the Canadian history pamphlets was not a victory at all, rather was a tragic and most notably, a terrible loss. The event is simply known as Beaumont Hamel. It was named after the small French village situated two kilometers to the north of where the battle took place. However, it is a misnomer to call what happened on that bloody morning as a ‘battle’. Rather, it could more aptly be defined as a massacre. On that morning 780 Newfoundlanders went ‘over the top’ against entrenched German positions. When the attack was over only 110 men returned unscathed to allied lines with only 68 available to stand for roll call the following morning. 324 men were either killed or missing and presumed dead. Another 386 were wounded in the attack. This equates to 91% casualty rate…the highest rate incurred by a single regiment in one battle in the war.

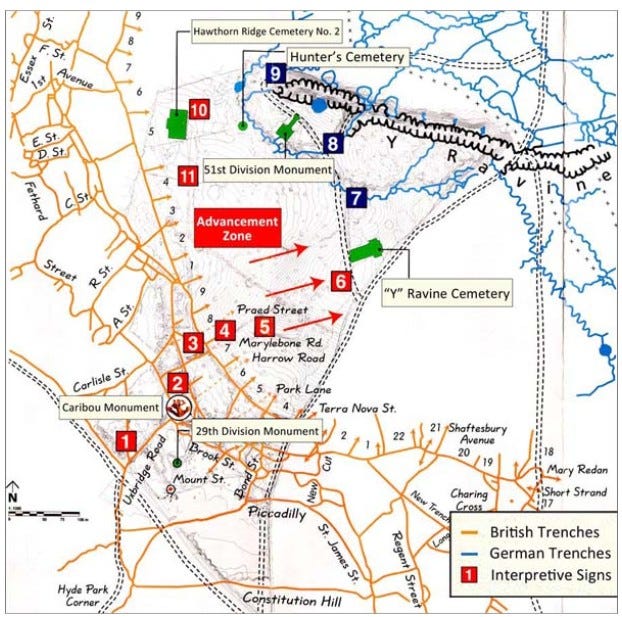

The statistics are deservedly atrocious and helped colour the ill-fated legacy of the Newfoundland Regiment. However, it is helpful to review the terrain and circumstances which contributed to leaving the field with such disastrous results. On the morning of July 1st, 1916, the Newfoundland Regiment moved into the front-line trenches located to the south of Hawthorne Redoubt and on the high-ground that look down upon the village of Beaumont-Hamel in the distance. For the seven days leading up to the day of the attack, gun teams in the rear hammered German lines with a continuous array of high-explosive ordinance. These shells were designed to be anti-personnel, where they would explode over the battlefield and send shards of shrapnel coursing through the exposed bodies of any unlucky defender. However, there were no ‘exposed German defenders’ manning the lines. The German Army built bunkers deep into the chalk and far enough into the earth that they were perfectly safe from the assault exploding just above them. These bunkers were reinforced by wooded beams and large enough to comfortably safeguard the platoons and units assigned to the sector. In addition, the explosives chosen for the bombardment had fuses that caused the shells to explode above the ground having little or no impact to the thick nests of barbed wire lain throughout no man’s land. The impact for these oversights of imagination caused tragic results for the Newfoundland Regiment when the whistles blew at 9:15 am.

Before we join the first waves of men ordered to advance, we should revisit the front two hours before zero hour. At precisely 7:20 am a massive mine was exploded under the Hawthorne Redoubt. The earth under the German trenches situated through the ridge line exploded skyward and creating a crater 130 feet wide and 60 feet deep. Minutes later thousands of men from British brigades rushed forward and advanced towards the German-held positions to the right and left of the newly former crater. The Newfoundlanders, however, did not. The battle orders, in anticipation of the mine rendering the German defenders either dead and buried or stunned, expected that the Newfoundlanders would be able to advance at a leisurely pace. Add to this fact that the communication trenches which led to the front lines quickly became clogged with men both moving forward and other wounded men being carried back towards the medical stations situated in the rear. Despite their readiness and eagerness to advance, the Newfoundlanders just had to wait their turn, and time ticked on.

At 9:15am, the Newfoundlanders finally received their orders to attack. The jumping off trenches were located at a flat portion of the line at the summit of a long, steady decline. The German front lines were about 300 yards in the distance at the bottom on the hill. To the surprise of the leading waves, they quickly discovered that after seven days of bombardment, all of the wire was undamaged. And to an even deadlier surprise was the fact that most of the Germans holding the front lines were not killed from the exploding mine, rather were perfectly fine and holding the line in their entrenched machine gun nests. Like being caught in a ghastly parade, with each yard that the Newfoundlanders advanced more of their men were cut down by the machine gun fire. From their imbedded positions, the Germans has an open and clear view at the advancing troops and were able to cut the men down with cavalier casual ease. It was a bloodbath and a massacre with the glory of the island of Newfoundland extinguished in less than 30 minutes of time. Survivors were only able to return to the allied lines by crawling over the bodies of their brethren. It was a tragedy beyond tragedies.

Later that day and into the evening, the adjutant was resigned to the brutal task of compiling the list of dead, wounded and missing. Private Lind was listed as being missing in action. This was changed when a fellow soldier was interviewed a few days later. He noted that he passed Lind as he advanced through the mess of wire and dead. He remembered seeing Lind, on the ground, buckled over and holding his stomach. Moments later, he was wounded and when returning, again saw and recognized Lind, immobile and prone on the ground as he himself struggled to return to the safety of his allied lines. With that visual confirmation, Newfoundland’s treasure and national blogger was confirmed as being killed in action.'

The Battle of the Somme was not one battle, rather was a series of operations conducted along a forty-kilometer front between July 1st, 1916, and Nov 1, 1916. It was an intensely bloody event where the Allies lost 420,000 men with almost 96,000 paying the ultimate sacrifice. Incredibly, 19,420 British soldiers were killed on the very first day…most in its’ first few hours. The Newfoundland Regiment received the designation of Royal Newfoundland Regiment resulting from their service at Gallipoli and Beaumont Hamel. While their casualty count represents a very small percentage from the overall British/Allied cost, it did however, represent a huge contribution from a relatively lightly populated island colony. In 1925, the land where the battle took place was gifted to the colony of Newfoundland by France for it’s perpetual use as a memorial to honour those lost both on the 1st of July 1916 and in all theatres of the conflict. At the hill’s summit, on the exact spot where the regiment began its’ advance a sculpture of a caribou was erected signifying the heritage of the men who gave their lives in the cause of King and Empire. Visitors, Canadians, Newfoundlanders and all those interested in remembering to never forget are encouraged to visit the Beaumont-Hamel National Historic Park. At the base of the memorial is a plaque that lists the names of 820 Newfoundlanders who gave their lives in the cause of liberty are a reminder of their service and sacrifice.

Remember them. Remember Private Mayo Lind.

Note: The letters written by Francis, Mayo Lind were later compiled and published into a book named, The Letters of Mayo Lind, (Robinson and Co. Ltd, 1919). It is available free to access and read online.

Resourced used in the research of this bio

The Forgotten Campaign, Newfoundland at Galipolli, Tim Cook, Mark Osborne Humphries

The Newfoundland Regiment at Beaumont-Hamel by David Parsons

https://ngb.chebucto.org/NFREG/WWI/ww1-regt-triv-battle-bhamel.shtml

https://www.heritage.nf.ca/first-world-war/articles/newfoundland-regiment-at-gallipoli.php

https://rnfldrmuseum.ca/